There are few places in the United States that are as frequently challenged by the immediate and increasingly urgent impacts of climate change as New Orleans, Louisiana. The low-lying city has been an emblem of climate change driven ecological risk for decades, and recent storm seasons have only made these issues clearer and more threatening. Developing a functional relationship to rising sea levels is a matter of survival not just for a single neighborhood or community, but at the scale of the entire city.

Claire Anderson, CEO and founder of Ripple Effect, understands this, and sees water literacy as a vehicle for helping the next generation of New Orleans residents to understand both the issues facing their immediate community and global climate change more broadly. Ripple Effect develops curricula and tools that train teachers and students to understand the systems and infrastructure that will be most impacted by climate change, and develops innovative proposals and solutions to address rapidly evolving climate issues and challenges, and while this approach is rooted in local concerns, it may serve as a model for other environmental education organizations in communities across the country that are increasingly experiencing the impacts of climate change

Siegel has been a supporter of Ripple Effect’s work since 2019, and recently concluded a round of funding for their education and curriculum development programming. In this ED Q&A, we reflect with Claire on what’s next for the organization, and how their work fits into a broader understanding of infrastructure, sustainability, and climate resilience.

Siegel and Ripple Effect began working together in 2019, and a lot has changed since then. How have the events of the past few years impacted or reinforced the way you approach your mission-driven work?

The last few years have shown the chasm in this country between perception and reality. We saw a lot of systems fall apart that, as Americans, we assumed were strong – perhaps even the best in the world. We saw some very, very big cracks in our public health and education systems, in our democracy, and in the ability of our government to create effective solutions at the necessary speed and scale.

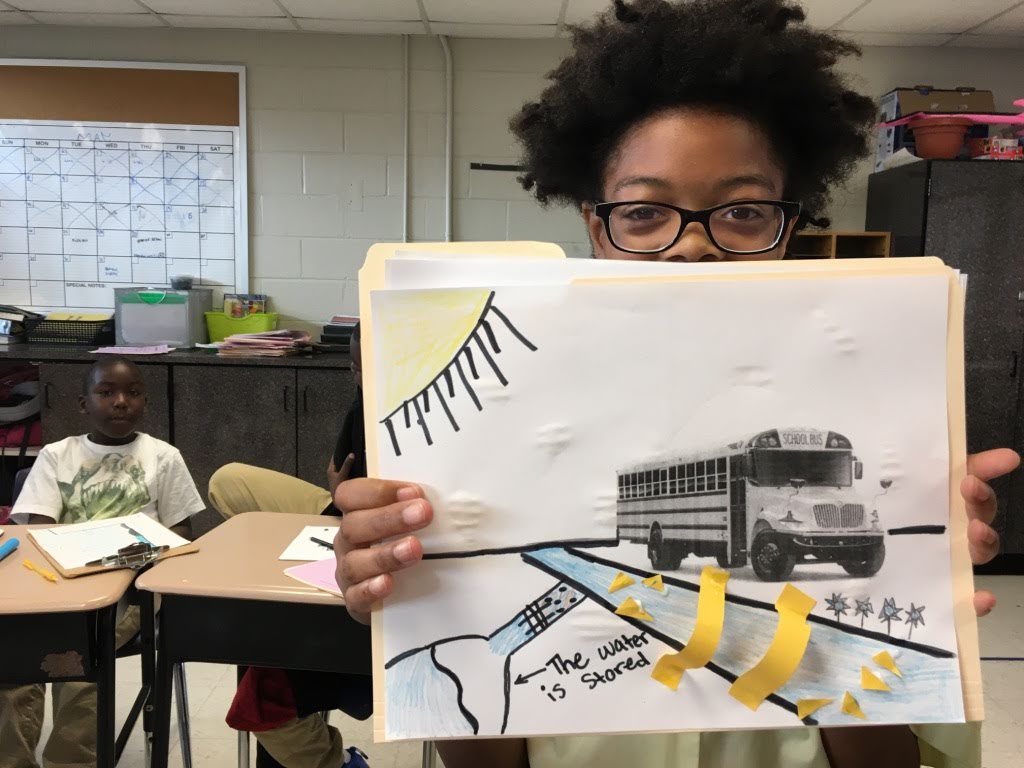

At Ripple Effect, this kind of exposure led us to double down in our seriousness around impact. We’ve had to develop systems for tracking our capacity to deliver all of the things we say we want, such as inquiry-based science instruction, growth of students’ ethical reasoning, scientific knowledge, and the ability to draw on and synthesize Western modern science and traditional ecological knowledge. We’ve gotten very specific about how our progress towards these goals is actually manifested in our work. This has meant more clearly defining the outcomes we want to see in classrooms, and creating systems for measuring and assessing those outcomes.

Thankfully, this is the language of our school partners, too. It’s not enough to just focus on improving teacher practice; how does growing a teacher’s capacity to, say, facilitate a classroom discourse about the justice dimension of a local water issue, impact student understanding of the issue or their sense of agency?

When we started this work, I think I had this notion that we would “launch” this organization simply by raising money for what we already knew how to do. But now, because we’ve taken the time to build processes around incorporating education research and run smaller pilots with small groups of teachers, we’re in a better position to add value by helping schools run very robust water literacy programs that bring together a more comprehensive set of components – curriculum adaptation, a teacher fellowship, professional development for school leaders and curriculum leads, assessment design, and teacher development.

Water literacy means you have the knowledge, skills, and ethical reasoning necessary to effectively tackle water issues that are brought about or exacerbated by climate change. Increasing severity of major storms (like hurricanes), sea-level rise, land loss, and urban flooding are all due to the fact that precipitation patterns are changing because our planet is warming. All of our instruction is anchored in a real-world issue that’s impacting communities today. Students are introduced to a storyline, and lessons about history and power are embedded in the ways that water is controlled and distributed. There are lots of opportunities for students to engage dozens of adjacent topics through learning about water.

For example, it’s very natural for students to start thinking about the justice dimension. They might consider what can be done to improve this situation, and by making tradeoffs and tough decisions, they’re able to build new capacities around critical thinking and ethical reasoning. Students could also potentially move into the realm of economics, and learn about how markets play a role in decisions about water management. They could move toward social, cultural, or even artistic inquiry. They could also focus on infrastructure — not just thinking about building new stuff to account for sea level rise, but also reckoning with aging infrastructure, and the many decisions that went into designing and building that infrastructure in the first place.

I want the future generation to recognize the importance of those inquiries, to seek truth in exploring them, and to be ready to make some very, very tough decisions as climate change continues to force these kinds of society-shifting moments.

How do you see Ripple Effect’s work playing out across all three dimensions – physical, digital, and social – of infrastructure?

Because so much of our work has to do with physical infrastructure, we’re asking students to think about both how we can responsibly build new things to account for sea level rise, and also how we reckon with aging infrastructure, and the many many decisions that went into designing and building previous generations of infrastructure in the first place. The Mississippi River is an excellent use case. Historical attempts to control it have had all kinds of unintended consequences, including changing the natural course of the river and depriving wetlands of much needed sediment deposits— one of the main contributors to the incredible rate of land loss we’re experiencing along the coast. There are many lessons we can draw from the world around us right away.

We also see value in thinking about schools as a form of social infrastructure, much like the libraries example proposed in Siegel’s first white paper. There are natural forms of community overlap already happening — multiple generations, different families, different neighborhoods. There’s also, of course, the neighborhood around the school itself. For many schools, there can also be a layer of trust between school leaders, teachers, and parents that could be helpful for sharing information, co-learning, and building community-level resilience for before, during, and after a flood or storm event.

Finally, we are interested in exploring how teacher decision-making could be supported by some form of digital infrastructure, specifically, thinking through how a digital interaction could support them in analyzing and responding to student understanding in the moment, whether that takes shape as student work, discourse, or assessment data. But before we jump to solutions, we want to ensure that we have fully defined a very specific problem in the real world before we attempt to digitize any of those pivot points.

You can’t tackle this work at any meaningful scale without up front partnership and buy-in from public schools and the individuals who work in them. Co-design is a must. Too much is still unknown and untested when it comes to effectively teaching kids about climate issues, particularly those that bring to the fore questions around economics, history, and social and political issues. Any program coming from the outside, while potentially very good, isn’t going to produce the kind of profound shifts in student learning that we need to really prepare them to tackle such complex challenges as those brought about by climate change—not unless the program is truly, fully embraced and “baked into” the way schools and teachers conceptualize the work happening in classrooms. Even though environmental education and environmental research are hugely important for the next generation, we still need to do this work in a way that resonates with how schools and students actually operate.

What needs to change at a systems-level in order for this work to be as impactful as possible?

When I reflect back on my experiences teaching, and when I talk to teachers today, I’m struck again and again by how difficult it is to be a great teacher.You can’t just walk into your classroom and deliver a lesson. It takes an enormous amount of preparation—even more so now that a majority of states have adopted Next Generation Science Standards, which represent nothing short of a sea-change in science education. Instead of a very didactic approach, which is how most adults learned science growing up (very focused on memorizing facts and vocabulary) the emphasis has shifted squarely to inquiry, aka, doing science just like real scientists do, and using science practices to ask and answer questions about complex, real-world phenomena.

So what does it take for a teacher to be great at that? Ideally, you’ve taken some time to anticipate how students will respond to that lesson and are ready to respond to many potential outcomes. You have the skills to cultivate a classroom culture where students are learning from one another. This takes time and in-depth preparation, discussion, and co-planning with peers. Giving teachers the time, tools, and space that they need in order to do this kind of preparation has the potential to be enormously impactful for students and school communities as a whole. Scaling any successes requires that K-12 stakeholders place value on seemingly-small, incremental shifts, because, in such a complex endeavor, there is no silver bullet.

Claire Anderson is co-founder and executive director of Ripple Effect Water Literacy Project, a New Orleans-based environmental education nonprofit whose mission is to empower the next generation with the knowledge, skill, and ethical grounding they need to strengthen communities in an era of climate change and sea-level rise. The organization partners with school districts and charter networks to provide wraparound support for water literacy course development—including curriculum design, assessment design, and teacher professional development—for schools that want to incorporate locally relevant water issues into their everyday science instruction. Ripple Effect has expanded from elementary to middle and high school, and is growing its reputation as a boundary organization that thoughtfully integrates educational research with on-the-ground realities of classroom teaching, with particular focus on addressing the needs of Title 1 public schools. In 2020, Claire conceived of and led facilitation for a region- wide interpretive planning process to define a shared vision for justice-centered water literacy, including establishing a consortium of leading environmental education organizations, and engaging with over 70 educators, water researchers, practitioners, and community members across South Louisiana. Currently, the organization is focused on three multi-year initiatives with New Orleans-based charter networks and teachers, with support from the National Academies of Sciences. Claire is a member of the Education Advisory Board for Louisiana Sea Grant. She lives in New Orleans with her husband, John, and their pit bull, Rosa.