With over a Century of Planning Under its Belt, RPA’s Leader Reflects on its Unique Approach and Ongoing Impact

The most successful and sticky policy ideas take into account an entire region and the various stakeholder groups, consider long-term impacts, and cut across siloed areas such as transportation, housing, infrastructure, governance, energy, and the environment. That’s the thinking behind Regional Plan Association (RPA), the highly respected independent, nonprofit, civic organization that has worked toward better policies and long-term planning in the tri-state region for over 100 years.

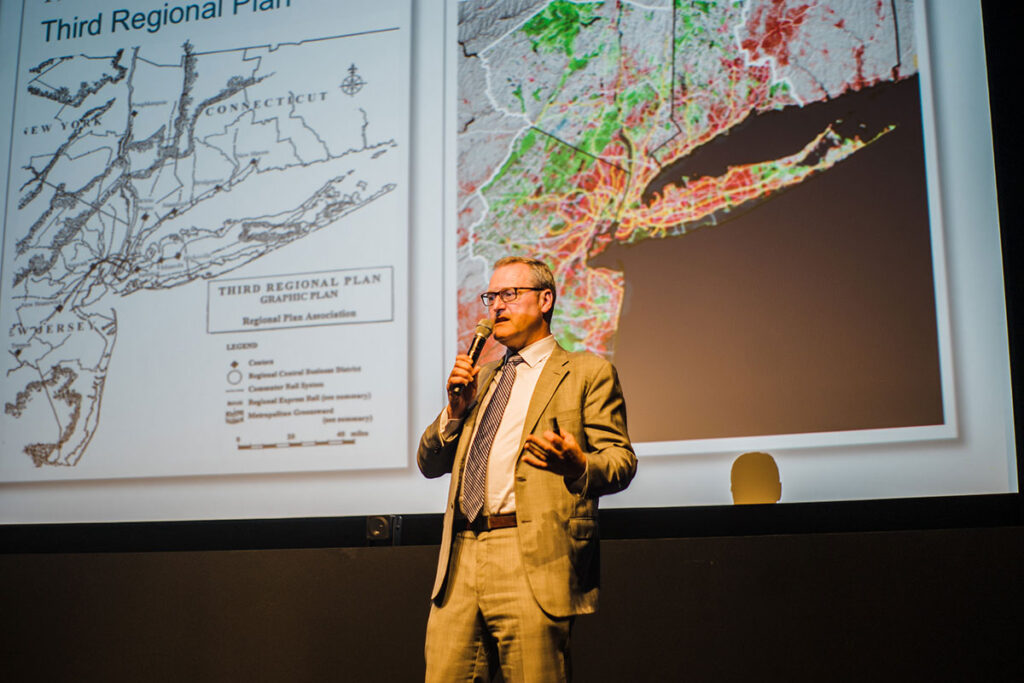

As RPA holds its annual Assembly to convene stakeholders across the region this week, we sat down with RPA President and CEO Tom Wright to discuss RPA’s unique approach, the battles it’s fought, and the partnerships it’s built. Along the way, Tom explains how RPA is a little like a submarine, why the solution for better airport access lies in looking west, and how and why RPA works to promote ideas whose time has not yet come.

As indicated by the Regional Plan Association’s name, you take a regional approach, and you’re committed to long-range planning. In addition, you operate outside of government, but are deeply interested in and connected to the work of government. How and why did RPA adopt this approach?

The Regional Plan Association is a unique undertaking and I’m often curious why there aren’t more RPAs around the country or around the world.

It was 101 years ago in the spring of 1922 that a group of civic, political, and business leaders came together to talk about undertaking a first regional plan for the New York metropolitan region of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. In the two decades after the creation of a Greater New York City, the consolidation of parts of Long Island and Brooklyn, Staten Island and Southern Westchester into the five boroughs, the city had built the subway system and bridges across the East River and become the great gateway to immigrants from Europe. Its population was growing exponentially.

The group that met in 1922 had this idea that there needed to be a plan for not just the five boroughs of the City itself, but the entire metropolitan region. Interestingly, rather than try to create a public sector entity to do it—a federal, or state authority—they thought the way to do this would be through a civic institution, not to try and replace the public sector, but rather to be outside of it, giving guidance on what we think should happen.

I used to think that my job at RPA was to put myself out of business. If we could create good plans and policies and recommendations and get governors and mayors and other elected leaders to follow them, then we wouldn’t need an RPA. But what I’ve come to believe after more than 20 years working here, is that the issues that we’re working on are regional in nature, so they’re going to transcend political boundaries. We include parts of three different states, 31 counties, 782 towns and cities—of which one is New York City and 781 are not.

Could you provide an example of how RPA’s positioning outside of government and its regional and integrated focus has resulted in better policy recommendations?

A priority for us today is the Gateway Tunnel, which would connect New York and New Jersey. I still find myself in almost daily conversations with public and elected leaders, or civic leaders, who say, “Why are we building that tunnel to the other state?” The answer is, “We ought to be doing something because you both benefit from it.”

Another unique thing about RPA is that we don’t look at just transportation or just housing or just economic development or just climate. We look at all of them together. [As a non-governmental entity] we have the ability to work outside the silos. We have deep expertise in many of those areas.

We understand that you don’t build a new train line just because you like choo-choo trains. You build it because you want to provide opportunities for jobs or housing, or other things. You need to think about the interaction between those issues.

RPA also takes a long-term perspective, which is fairly unique in your field. Why is that important?

[We’ve taken that long-term approach throughout all of our regional plans, from 1929 forward.] For example, in 2017, we released a plan that identified priorities for the next generation. We looked at trends we see in terms of demographics, economics, technology, climate, etc. And we said, “Here are the recommendations that we’re making to address them.” None of these are recommendations that we expect to be taken up and passed by the current mayors and governors and elected leaders that we’re working with. They’re going to take longer than that.

When you put together those three components—the regional and metropolitan perspective, the cross sectoral issues, and the long term perspective—none of that works within the public sector structure. It’s important that we are a private, non-profit, civic organization outside that political structure.

At the same time that RPA is outside of government, you also work frequently with government. What does that relationship look like?

The relationship to the public sector is really an important one. We have to have our independence and the ability to say “no” when we think they’re making mistakes. We don’t look for fights with the public sector, but we don’t shy away from them either.

We often disagree with public officials. But during my time at RPA, I can think of only one major battle we’ve had with a public official. New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and his Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff proposed a new vision for Manhattan’s West Side, including development of a football stadium on the Hudson Yards themselves. We thought that that was a waste of a very valuable public asset. It would threaten the Broadway and cultural industries in New York because of the traffic it would bring. And it was just a poor use of publicly owned land.

We led a real campaign against the proposal. It was hard to do, because it was an administration we agreed with on many other things, people we liked. There was nothing personal about it. But we felt like we needed to stand up and say, “This is a mistake.” Ultimately we were able to convince other legislators that we were right and they killed the project.

Independence from the public sector is really important for us. I prefer it when I don’t have to fight with them. There’s always also an inside/outside game. There are times that I will find myself quietly talking to an official or an elected official to say what we think about a policy, hoping that they will change course so that later we won’t have to go public with our criticism.

I’m very fortunate, when I look at the folks that I work with across administrations—deputy mayors, and commissioners in city hall, and state officials in all three states working on housing or transportation and their heads with the public authorities—I have extraordinary respect for these people. They are smart, well-intentioned people, by-and-large doing an excellent job. It’s more about trying to consult with them and guide them rather than creating an “I’m right, you’re wrong” dynamic, which is much more productive.

Does the expertise that you offer and your regional perspective ever give public officials cover to take a position that may be unpopular?

Definitely. I once was in a conversation with an elected official and we were recommending voting against the proposal for the football stadium on the West Side during the Bloomberg administration. This person said, “If you want me to climb out on that ledge, you’ve got to go out there first and show me that there’s room to stand on, and that I will not fall off.” I thought, “That’s exactly right.” That’s really my job.

RPA is set up to take that heat. Our funding is diverse, our governance is diverse. Our board members aren’t tied to one administration. We can take controversial positions and survive even if we make some enemies.

Another example of this came with the Bloomberg administration. To their credit, they were willing to work with us even after we opposed the West Side development proposal. They started an effort that became PlaNYC, the first long range sustainability plan for New York City. I told the administration, “What you’re proposing is the right stuff. But a lot of this is going to be very controversial. You can think of me as the cannon fodder. Let me take the criticism so it’s easier for you to do what you want to do.”

Besides governmental officials, are there other stakeholders that you involve in the process of recommending and developing policies?

In the 1920s when RPA was founded, during the Progressive Era, there was a belief that technocrats could solve all the world’s problems. In the 1960s—and I credit my predecessors at RPA—the leadership became concerned about what was happening with segregation in America, particularly in metropolitan regions. White, upper middle-class families were moving out of cities into the suburbs and creating new segregated enclaves. In response, RPA really started experimenting with trying to bring more voices into the planning dialogue.

In the early 1970s, as part of the second regional plan, we put together a documentary series called Choices for 76, which included people explaining what was happening with suburban flight, tax spaces, traffic, congestion, affordable housing and other issues. These conversations were conducted frankly, in very progressive terms about issues that were often being whispered about. Unfortunately, RPA wasn’t very successful in combating those challenges. We went through a period of urban decline and disinvestment and it really wasn’t until almost a generation later that we started to see a kind of rebirth and renewal and revitalization.

At RPA, we’ve always understood that the only way to do the kind of planning we’re talking about is to also include grassroots organizations. A good example of this is the Ford Foundation’s support for our Fourth Regional Plan. We came to them with a proposal to take half of the money that they gave us and grant it to grassroots organizations—immigrants rights groups, local housing groups, and others—to participate in the regional plan process. Our belief was that we needed to empower those organizations and bring them to the table to discuss decisions and policies that they usually weren’t in the room for. It was also about informing the process. These were the communities that we were trying to help the most. We really needed to understand their perspective.

As an example, because of the input of these groups, our transportation recommendations included talk about informal transit options. We even talked about voting rights at a local level and how allowing non-citizens to vote in local elections was important.

We also have more understanding of these communities and the challenges they face. We can pinpoint communities of lower-income, communities where people don’t own cars, communities that are vulnerable to sea level rise, communities that are transit deserts or food deserts. Often a lot of those factors overlap each other. Pinpointing those challenges allows us to think about how we can help those communities. My goal here really is to try and help the communities that have been left out of economic opportunity or that remain segregated and cut-off.

Could you give us an example of how you’ve engaged grassroots organizations representing multiple stakeholders to develop and advocate for a particular policy position?

We’ve been advocating for a housing plan in New York state. Unfortunately it failed recently. But the idea was to try and get the suburban communities to open up and allow more multi-family and affordable housing, especially around train stations or accessory dwelling units, to change zoning codes, and to have enforcement mechanisms around it, too.

To do that, we were working with grassroots organizations in many of those communities, especially in Long Island and Westchester. They have local knowledge. They have political influence. That’s an important part of what we do today at RPA—to try and find common ground with groups. We’re a regional organization, but that work is built up from the local communities.

Even though the legislation failed, we were able to change the conversation. We concluded that over the next decade, New York State in our region needed 816,000 additional units to address the demand and the population and economic growth we projected. We put our number out with all of the background about how we calculated that figure, and it became the way people talk about housing.

Does RPA ever face criticism because you are representing the entire region rather than a specific locale? How do you address that criticism?

I’ll kind of go to a meeting in New York City and people say, “You’re that suburban group, you’re always trying to help out New Jersey.” At an event in New Jersey or Long Island, people say, “You’re those Manhattanites. You’re trying to turn us into urban communities.” I figure if I’m getting criticism and equal measure, I’m probably doing well!

We can’t make everybody happy. We have to make sure we’re reaching decisions because we think that they’re the right ones. We try really hard to balance those things. The fact that we have a very strong internal research team helps with this. So when we talk about these issues, we’re not doing it as an organization that’s putting feelers out to find out what other people say and then basing what we say on that. We are doing our own analysis, our own empirical research about what economic trends and demographics mean, whether we think models hold up.

When we make public comments, public officials, civic partners, the media, and others know that we can back up our position. It’s based on objective analysis, not simply a political calculation.

At the same time that you’re developing these long range projections and plans, events often change around you. How do you remain nimble and responsive to those changes while still planning for the long-term?

For us, the regional plan is the North Star. It gives us an opportunity to put out a range of ideas, some of which may be incremental and fairly easy to do in the next year or two, and some of which are so crazy that they’re going to take decades to do.

An example of the latter is congestion pricing to pay for the transit system. We said that we should charge every car coming into the region, and use the pricing mechanism to try and keep demand within the capacity that we have. We began advocating for congestion pricing in 1996, five years before London created its congestion zone. We’re hopefully very close to seeing that put in place in New York City next year, a quarter century after we first advocated for that policy.

We don’t shy away from proposing things that are going to fail several times, before they, before they actually take root. One of my colleagues, Jeff Zupan, likes to say, “Our job is to propose ideas whose time has not yet come.”

That said, we also have to adjust to what’s happening in current events—for example, a 9/11 or a Superstorm Sandy or a Great Recession. You have to say, “We had predicted that things would go this way. This is going to put a major wrench in the works. What are the new priorities that we ought to think about?” Or do we take a look at it and say, “What we were saying before still holds. And we’ll stick with it.”

The analogy I like to use is that submarines have two types of guidance systems. They have a gyroscope—a spinning ball that can tell the crew how fast the submarine is going and what direction it is going. Every time they change course or velocity, it records that. It’s an internal guidance mechanism. The gyroscope is a navigation system that allows them to know where they were, they know where they’ve gone, and know where they’re going.

At the same time, the submarine is sending out sonar. They’re bouncing sound waves off of all of their external things. Then as those sound waves come back to them, they measure them. That gives the submarine crew a picture of what’s happening out there.

At RPA, we have both gyroscopes and sonar. The gyroscope is the Fourth Regional Plan. It’s the blueprint. We said that these were the important things that we needed to deal with over this generation. Current events happen. And that’s where the sonar comes into effect, because you have to look for the opportunities that are afforded based on what’s happening externally.

Apart from the Fourth Regional Plan itself, are there guiding principles that remain constant for RPA, even as current events and circumstances may shift?

We spent a lot of time as a staff and with stakeholders developing core values that drive everything we do at RPA. They are prosperity, sustainability, equity, and health. We score every recommendation as to how well it does in achieving positive change in all four of those areas.

We also have four buckets of recommendations in the Fourth Regional Plan: making the region affordable for everyone, rising to the challenge of climate change, fixing our failing public institutions, and creating a modern, customer-oriented transportation system. Those became the rubric for those 61 distinct recommendations that we made in the Fourth Regional Plan.

We go from the very local and small-scale up to the very big projects. Often on big projects, we are the unique organization that has a regional perspective and is not operating in support of a particular city or state.

A good example of this is with the airports. In the region, we have LaGuardia, Kennedy, and Newark airports. They need to function as a system. After 9/11 there was a lot of focus on Lower Manhattan. There were a bunch of business folks, well-intentioned former public officials, who were all looking to the east, asking, “How do we connect to Kennedy Airport?” They came up with a really complicated project, which would have taken an existing subway tunnel that was carrying around 80,000 daily passengers at the time—mostly people of color working in kind of support services to office buildings. It would have converted that subway line into a Long Island Railroad connection that would have gone out to Kennedy Airport, to serve 7,000 executives a day instead.

It was a terrible idea. It made no sense. You’re going to spend billions of dollars to reduce the capacity of the system. You’re going to preferentially treat the people who don’t need the preferential treatment and hurt other communities. It all stemmed from the myopia of not looking at the entire region of Lower Manhattan.

The best way to get to an airport from Lower Manhattan is not to go east, but to go west out to Newark. The PATH train already runs from Lower Manhattan out to downtown Newark. If you just extended another two miles out to Newark Airport, you would have a great connection. We’ve spent the last 20 years promoting that connection.

This week you’re hosting RPA’s annual Assembly, a virtual and in-person convening of policy experts, public officials, and business leaders. How are you planning to realize some of the goals and approaches that you described in our conversation during the Assembly?

We’ve found that it’s really important to bring together. There are lessons we can learn from other cities and metropolitan regions, so we bring in outside experts. But just as important is bringing together the folks who are working on these issues and giving them a chance to meet all of the other people who are working on these issues.

Take something like the Gateway Project. We have folks from New York and New Jersey, and also Connecticut and the federal government, and people from Pennsylvania coming up. We will have the engineers and architects working on it, and also the real estate folks, and the people working in city planning, and the community board. They’re all in the room together. It’s a chance for people to talk.

The panels on the stage will be amazing. This year we have Senior Advisor to the President Mitch Landrieu and Senator Cory Booker as two of our featured speakers, for example. But the biggest thing about the Assembly is not what’s happening on the stage but that people are able to make connections and talk about these issues with the other folks in their world, especially across the entire metropolitan region. There have been cases where we’ve planned regular conversations between key officials throughout the region so that they could talk about issues. In many cases, they had never even met each other before.

####

Tom Wright is president and chief executive officer of Regional Plan Association (RPA), the nation’s oldest independent metropolitan research, planning and advocacy organization.