This is part of our “Designed for Scale” series, which explores how we can design and fund programs that are prepared for the challenges of expanding their reach and delivering broader social change.

Scale is seen as one way to reduce costs, with investments yielding a greater proportion of returns as they take on greater reach. But going bigger on scale doesn’t always correspond with reducing costs. One area where we’ve seen this in the starkest relief is in education, and in particular, learning over one’s lifetime.

If you want to train more workers today, there are plenty of options. But if you want to sustainably finance worker education, the subject becomes more complex. When relying entirely on corporate or philanthropic sponsorship, successful training programs can become victims of their own success. They may be forced into downsizing educational resources as they scale up their reach. Or they might sustain those resources by raising costs – skewing toward students who can afford the risks, loans, and/or time away from work or family obligations.

So how do you build a successful worker education program that can also scale?

Student-Centric Scale

We’re exploring different possibilities to extend benefits to more lifelong learners and expand educational opportunities in sustainable ways. When it comes to financing and sustaining these programs, scale is at the center of our attention – and in this case, student-centric scale.

Typically, the burden of financing skills falls on the trainee. This is true of traditional degrees, and equally true of skills certifications and updates that can keep workers at evolving companies, or ensure those skills are there where needed over the course of a full career. When a trainee takes on all of the financial risks, they have imperfect information about what skills are in demand and what employers are hiring. Meanwhile, a factory may have a specific need and be open to training new hires, but can’t find eager applicants. Finally, schools want to know what kind of training is most in demand and effective.

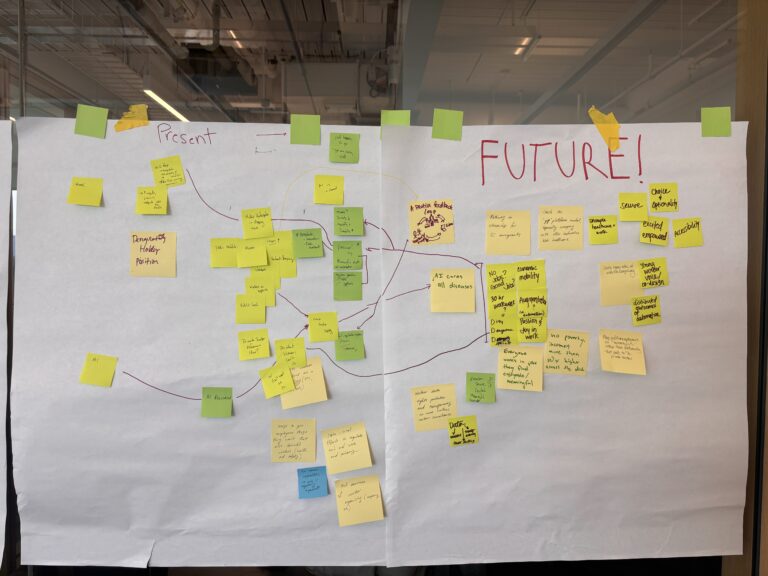

If you were to look at this system from a different vantage point, you might see the relationships between these pieces:

- The trainee, who is seeking viable skills but may not be able to afford it (or is wary of making a risky investment into a training program)

- The workplace, which needs a skilled workforce, and wants to innovate while avoiding turnover and displacement

- The schools themselves, which want to create effective, useful skills development

The pieces of the puzzle are there, so how might we arrange them to both preserve equitable education opportunities and achieve scale? When we acknowledge that a student’s skills would benefit all of these stakeholders, how might we design incentives for workplaces and training centers and work to remove access to barriers?

COOP Careers: Scale Beyond Dollars

COOP Careers offers a tuition-free digital skills training program designed to cultivate connections with their peers. Without tuition, there’s a lower barrier to entry, as learners don’t have to take on debt. However, more learners means they need more financing. So how has COOP built their model to scale?

COOP realized that the main thing they needed to scale wasn’t necessarily money – it was training hours. Money is one way to solve the problem of finding trainers, but it’s also a barrier to scale. On the flip side, recent alum might not have extra money to spare, but many have time. What if they could scale by collecting volunteer time instead of just money?

Each graduate of the program is asked to help sustain or expand the reach of the program through a “pay-it-forward” approach. Graduates can become coaches, mentors, or find other ways to support COOP’s operations through administrative or financial roles. In other words, repayment is oriented toward volunteering in ways that amplify the reach of the program, rather than paying for tuition. Roughly 10% of alumni connect to the program in this way, with some taking on full-time staff positions. This approach to scale focuses on graduates as a resource for creating more opportunities. In turn, it keeps overall program costs low. Without thinking about scale at the onset, COOP wouldn’t have built its culture of volunteerism that contributes to its ongoing success. You can read more about COOP in this Leadership Q&A.

Pursuit: Scale with Income Sharing

Pursuit is a social impact organization that helps low-income adults without college degrees launch tech careers, and raise their salaries from $18K to $85K on average. It has spent the last nine years connecting low-income Americans with career opportunities in the tech sector, including at companies like Twitter, Uber, and Citibank. Pursuit’s cohorts reflect the diversity of New York City: 70% are Black or Hispanic, 50% are women, 40% are immigrants, 55% are non-bachelor’s degree holders, and 100% come from low-income backgrounds.

Private and public funding for job training is and has been in short supply. Rather than rely solely on philanthropic funding, Pursuit planned for scale by launching the Pursuit Bond, an Income Share Agreement (ISA). An ISA differs from a traditional loan in that if a learner doesn’t secure a job or makes less than an agreed-upon amount, they don’t have to make payments. The initial cost of an ISA is provided up-front by socially responsible investors, and repaid by a learner only when they secure a job that meets the minimum income threshold. Because it’s only repaid if candidates are successful in reaching employment goals, this shifts the burden from the student to the organization managing their training. By leveraging capital markets, Pursuit is able to tap into a new source of funding that can meet its scaling goals.

Reflections on Scale

Alternative financing arrangements such as these represent a promising path to scale for these programs. But there are questions, too. Would these systems actually make access to career paths more viable for more people, particularly those who may not be comfortable taking on the financial risk of training today? If a program’s costs were tied to future earnings, how could that be safeguarded in ways that ensure economic opportunity rather than the status quo? Finally, do these incentives work to make training centers and programs more transparent? In theory, having better data about student outcomes could translate to better information for future students. The feedback could also drive programs to emphasize career readiness and opportunity placement — would that challenge the inequities of today’s education system, or reinforce it?

Our Scale Series began with the idea that scaling impact should be a core question for any organization from the outset, and asked what strategies were most important to each approach. We looked at two strategies: tapping into existing networks, and consciously cultivating a network that can support meaningful growth. These are not the only pathways to scale. But they suggest that planning for scale at the outset can create programs with greater resiliency.

When a solution doesn’t consider scale at the outset, it can constrain the ability to expand its impacts to more workers and communities. Programs that fail to consider strategies for scale could eventually find themselves victims of their own success.

Do you have more examples of how organizations are planning for scale? Please reach out to us at [email protected].

This reflection was written by John Irons, Senior Vice President and Head of Research and Eryk Salvaggio, Research Communications Consultant, and edited by Laura Maher, Head of External Engagement.