Reflecting our commitments to learning and knowledge creation, Siegel runs a Research Fellows program with the goal of supporting researchers asking how technology can be shaped and deployed in ways that better society across perspectives, disciplines, and sectors. Each year, we bring together those fellows in person for an annual convening, which provides a mix of structured and unstructured activities, as well as connections with our partner network. This year’s convening, which included 14 fellows, was held in New York City in mid-March.

The timing of our gathering this year felt significant. We gathered in the aftermath of the most significant divestment in U.S. scientific research in our lifetime, including a gutting of many federal grant programs that support our research grantees and fellows’ work, significant funding cuts to large research institutions across the country, and a chilling effect on independent technology research broadly. Our fellows are a group of interdisciplinary and largely early-career researchers interested in questions about building a more just future with technology. Their work in some of the most critical and forward-thinking fields had become precarious.

This context could have cast a pall over the gathering, precluding our ability to think toward a future where technology is designed, developed, and deployed responsibly. Yet, despite the structural and institutional walls seemingly falling in on this work, the room was filled with determination and hope. Fellows, clear-eyed about these new obstacles, approached their collaborative conversations with creativity and resilience, prompting us to leave the gathering with renewed energy to continue pushing for a just future.

Day 1: An Improbably Good Future

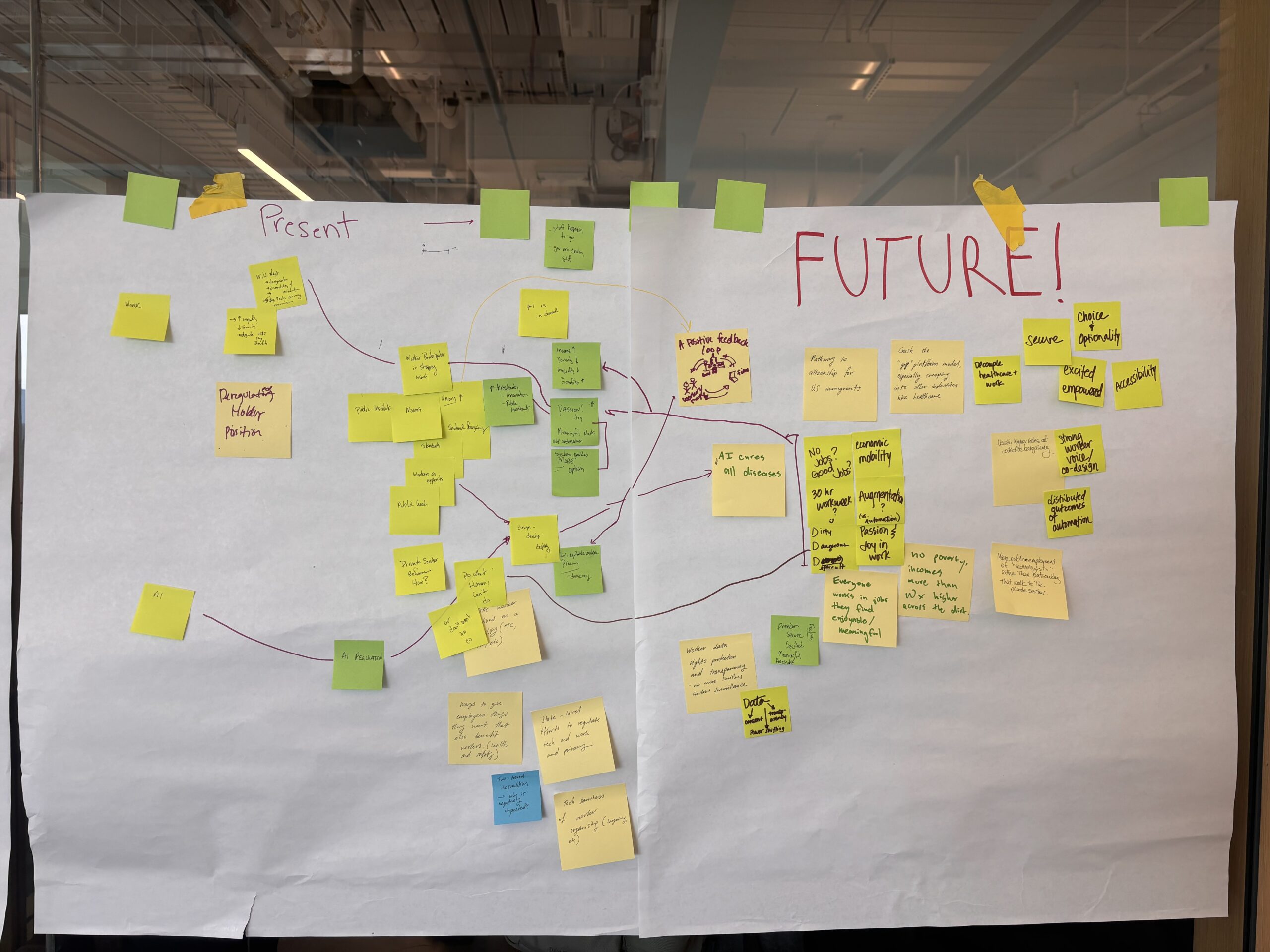

One of the core exercises was a small group workshop that invited the fellows to imagine an “improbably good future” for each of their domains, identify the present context and how it may enable or interrupt progress toward that future, and build a bridge of activity between the two. The animating questions for the exercise were, “Where do we want to go?”, “Where are we now?”, and “What would it take to get to a future we want?”. We will highlight some key insights that came out of each group:

Public Interest Technology Systems Building: Joy, Community, and Purposeful Problem Solving

How do you create communities that are curious and want to solve problems? How do you facilitate those conversations both offline and online?

Fellows in this group identified a need for curiosity about tech, rather than suspicion or distrust. Key takeaways suggest that the recent past and present of technology are marked by fear, greed, racism, individualism, short-term thinking, and are driven by profit and consumption. The group collectively imagined an alternative future centered on equity, joy, community, and curiosity, and where human problems were solved with intentionality. Ideas for building this future include making education and technology more accessible and humanistic, creating third spaces for innovation outside corporate control, emphasizing transparency, and fostering global and identity-affirming mindsets. The exercise really highlighted that creating a transformative, joyful tech future requires dismantling harmful legacies and building new systems rooted in reciprocity, collective identity, and purposeful problem-solving.

Community-led Design of Digital Infrastructure: Strengthening Trust and Civil Society

Which institutions can we trust? And how do we know? When do we know our institutions are beyond repair and we need to build alternatives?

Trust in institutions is something we can no longer take for granted. The group struggled to reconcile a desire to support existing institutions with the need to create alternative ones so as not to recreate the problems from which distrust emerged. The group noted that distrust can harm or help; for example, distrust in a monopolized information infrastructure can be helpful, while distrust of public education can harm. The group recognized this moment of uncertainty as an opportunity for creativity in our approach to designing governance built on community voice, democratic participation, and new incentive structures based on shared ownership models.

Despite the erosion of institutions, the group recognized the importance of the role of civil society as a lever in state and local policymaking. They also recognized that civil society is insufficient in its current capacity. There is a need to engage communities more effectively in these efforts and be a conduit of community voice on issues like privacy protection and data power. These approaches would also be strengthened by better defining what we mean by ‘community.’

AI and Work: Empowering Workers and Aligning Emerging Technologies with Labor-Centered Values

How can we get the right people in the room where tech is being built to give them the information and insights they need about the downstream effects on workers? How do we best partner individual workers and worker voice organizations with the companies making these tools?

According to this group of fellows, in order to achieve a better future for workers there are several core needs for the future: (1) agency for workers, (2) decentralized control and choice, (3) shifts in power toward more worker power, (4) elimination of worker surveillance, (5) data rights, protections, and data transparency for workers, and (6) commitment to augment labor, not replace it. Discussions also identified a gap between the design, development, and deployment of emerging technologies and worker needs. For instance, engineers working in AI labs may want to make pro-worker AI but lack the expertise to do it. They are unaware of the downstream consequences of what they are building and how it might be integrated into a workplace.

The group envisioned a future in which workers had a choice in their employment, a voice in how technology might impact their work, and found fulfillment and security in their work. To realize these goals, they identified the need to better define “good jobs”, increase opportunities for economic mobility, and enable higher rates for collective bargaining.

Day Two: The State of Independent Research

Fellows gathered on New York University’s campus, hosted by the Center for Social Media and Politics. We welcomed a group of experts to participate in a panel to discuss “The State of Public Interest Technology and the Role of Independent Technology Research”. The panel offered an opportunity to zoom out from our small-group conversations and reflect on the broader ecosystem in which this work is unfolding. Moderated by Cristiano Lima-Strong of Tech Policy Press, and featuring Wilneida Negron of The Future of Workers Initiative, Noel Hidalgo of BetaNYC, Catalina Vallejo of Social Science Research Council, and Nicol Turner Lee of The Brookings Institution, the discussion brought together a range of perspectives from policy, research, and advocacy. Much like our fellows, these leaders are navigating a rapidly shifting landscape—one in which the space for independent, public-interest-oriented technology research feels increasingly fragile.

The conversation surfaced a shared understanding that systemic support for independent research is both necessary and lacking. Panelists reflected on the growing concentration of power—both political and economic—that has narrowed the space for public accountability, particularly as private, commercial interests continue to dominate technology innovation. Many called attention to the importance of revisiting our history, not as a nostalgic exercise but as a way to build more authentic and sustainable structures for the future. One thread that ran throughout the discussion was the need to engage workers directly in policymaking, recognizing their lived expertise and capacity to shape technology in a way that serves the public good. Others pointed to a critical gap in funding and career pathways for early-career researchers and technologists who don’t fit neatly within traditional academic or industry roles. And while artificial intelligence is increasingly attracting investment and attention, there was a concern that this focus may be crowding out support for the kind of long-term, justice-oriented work that public interest technology demands.

Concluding Thoughts

Rather than offering a singular roadmap, the panel invited us to consider a set of questions and challenges that will require collective attention. It affirmed that building a future where technology serves the common good will take cross-sector collaboration, structural reimagining, and a recommitment to curiosity, creativity, and care.

In a moment marked by uncertainty and challenge, this year’s convening served as a powerful reminder of what is possible when determined, values-driven researchers come together. Across workshops and panels, we saw not only bold visions for what technology could become, but also practical, grounded ideas for how to get there. As independent, public-interest research continues to face challenges, gatherings like this underscore the urgency and value of building community, fostering trust, and supporting one another in the long, difficult, and vital work ahead.