This is part of our “Designed for Scale” series, which explores how we can design and fund programs that are prepared for the challenges of expanding their reach and delivering broader social change.

Today, there are 246,000 businesses that would fit the definition of a small-to-medium sized manufacturer. Taken together, they employ nearly half (44.4%) of the US manufacturing workforce according to Congressional Research Service. As we continue our series on scale, we turn to the challenge of bringing workers like these closer to decisions around innovation. To create a widespread culture of innovation in individual manufacturers – in other words, to scale a culture of innovation – we need to look at the levers that reach them.

Manufacturing Extension Partnership

Fortunately, there is a network in place. Created in the mid-1980s, The Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) was designed to help small-to-medium manufacturers identify and adopt new technologies through a blend of advising, sourcing, training and planning activities.

The MEP already has relationships with SMEs on a local level. There is at least one MEP in every state and Puerto Rico, supported by more than 300 small field offices. These local MEP centers are loosely coordinated through the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), but management of the centers is wildly diverse: state agencies, community colleges, or universities tend to be the primary partner, with input from NGOs, foundations and others. These MEP centers are typically arranged as private-public partnerships. Funding is supported by NIST but complemented, by design, through local contracts. Local, agile and responsive partnerships are essential to meaningfully engage in this work. In other words, if you scaled the approach of a single center, you would inevitably lose the benefits that come with hyper-localized responsiveness. A single good idea may not bring the same results to all, in all places.

As a system, though, the economic impacts of MEPs are clear. NIST writes that these centers have helped generate “$13.0 billion in sales, $2.7 billion in cost savings, $4.9 billion in new client investments, and helped to create and retain 105,748 U.S. manufacturing jobs.” One study found a 14-to-1 ratio of returns to investment in MEPs after 2020. The local-leadership model also makes them extremely agile. For example, in 2020 and 2021, MEP centers collectively pivoted toward supporting businesses during the pandemic, offering advice, grants and other assistance for a rapidly changing market, such as helping one California fashion startup pivot to face masks.

The structural arrangement of the network has spawned a diversity of approaches by local MEPs. Some states have a single MEP center, while others have multiple MEPs with scattered field offices. Some rely on universities or community colleges, others on a mix of state and local funding with private industry. Typically, these MEPs offer services to clients as part of their revenue stream. Strong local cooperation means offering the services local partners want. It also tends to create unstructured lines of communication between MEPs, which can limit opportunities for sharing successful approaches and programs.

Bottom-Up, Worker-Centric Scale

While it’s clear that MEPs have much to offer to American manufacturers, we’re interested in how those effects might make their way to the American manufacturing worker. Already, many of these centers are piloting approaches to innovation that build workers into the process. We’re still learning how and under which conditions those models work.

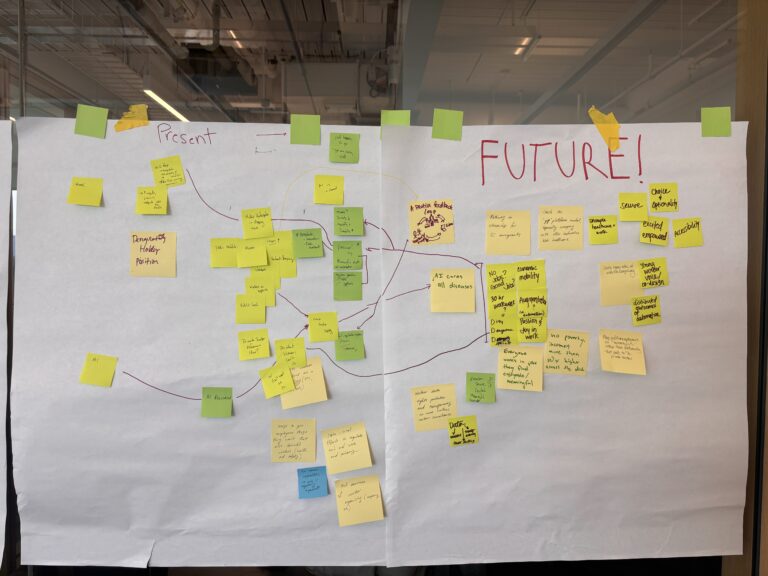

A recent case study from Siegel grantee Nichola Lowe, through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Urban Manufacturing Alliance, looked into the role MEPs are playing toward inclusive innovation in Buffalo, New York. Their work points to the ways local organizations and community partnerships can help “scale up” benefits of an MEP to include workers. They identified three pieces of a “collaborative inclusive innovation” cycle: centering organizations on different, occasionally overlapping populations; visioning, a creative and iterative process focused on co-design rather than top-down agenda-setting; and bridging, which is creating social infrastructure that encourages knowledge and resource sharing.

We see opportunities for this kind of expertise to serve as leverage for new approaches to innovation and inclusion far beyond Western New York. The case study is only the first of a series addressing how technology adoption could encourage more creative roles for workers, and how they might become partners in the design and decision-making around technology and innovation. How can workers be more involved in this innovation? Can MEPs offer guidance for integrating knowledge and creativity from the floor into the design decisions and strategies of the CEOs?

Ripple Effects Across the Network

We believe that the MEP network is in a unique position to make change at scale. Policies that move the MEP network toward embracing policies, skills training, and other services that are more in line with the next 20 years of workforce development will ripple out across its widespread constellation of centers and hundreds of thousands of workers. Key questions surround issues of communication and coordination. What are the best practices that might be shared across the network, and how could they be shared? What strategic shifts might become possible for the network as a whole – without compromising an MEP’s power to reflect on the local particulars?

By balancing participation and individual decision-making at the local level, but encouraging broader coordination and communication of approaches that work, MEPs could create a reinforcing feedback loop. By focusing on specific approaches at distinct levels of analysis – that is, at scale – we might arrive at an ideal balance between autonomy and coordination. This balance would ideally amplify the best results of localized approaches, while encouraging adaptation and experimentation with successful formulas that match the unique needs of particular communities.

Scaling Culture

As we contemplate the changing landscape of innovation and its effects on US workers, we wonder how a system designed for manufacturers might broaden its focus to the well-being of the American workforce and the communities they build. The answers could have big impacts on how US manufacturers innovate, and crucially, the workers whom they innovate with.

This reflection was written by John Irons, Senior Vice President and Head of Research and Eryk Salvaggio, Research Communications Consultant, and edited by Laura Maher, Head of External Engagement.